Welcome to Headstrong: a place to share my 20-year-old life with post-concussion syndrome (PCS). Here you'll find my stories, life hacks, and answers to (most) of your burning questions.

Welcome to Headstrong: a place to share my 20-year-old life with post-concussion syndrome (PCS). Here you'll find my stories, life hacks, and answers to (most) of your burning questions.

Recent studies have detected two distinct clinical subtypes of CTE: one group that presents with cognitive symptoms and one group that presents with behavioral/mood symptoms. Those with behavioral/mood symptoms tend to present symptoms at a younger age. Symptoms of each can include the following:

Memory impairment

Executive dysfunctioning

Trouble with attention/concentration

Language impairment

Visuospatial difficulties

Explosivity

Impulse control problems

Being “out of control”

Physical violence

Verbal violence

Disinhibited speech (inability to restrain/censor oneself in speech)

Disinhibited behavior

Social inappropriateness

Paranoia

Sadness/depression

Anxiety/agitation

Manic behavior/mania

Suicidal ideation/attempts

Hopelessness

Apathy

The differences in clinical presentations of CTE are not fully understood, but can be attributed to the different areas of the brain affected by different stages of CTE. CTE is diagnosed as stage I, II, III, or IV, with I being the least severe and IV being the most severe.

CTE is related to and caused by a buildup of protein known as tau, which is normally found in aging brains. In stages I and II of CTE, these proteins create neurofibrillary tangles in specific parts of the brain, the locus coeruleus and amygdala. The locus coeruleus influences emotion, stress, balance, and cognitive control, while the amygdala is involved in memory processing and decision making. Stages III and IV show degeneration of other parts of the brain, the hippocampus and frontal cortices. The hippocampus is important to memory, and the frontal cortices control cognitive skills such as emotional expression, problem solving, memory, and language. The parts of the brain impacted by CTE and their functions correlate with some of the behavior and mood symptoms outlined above (1).

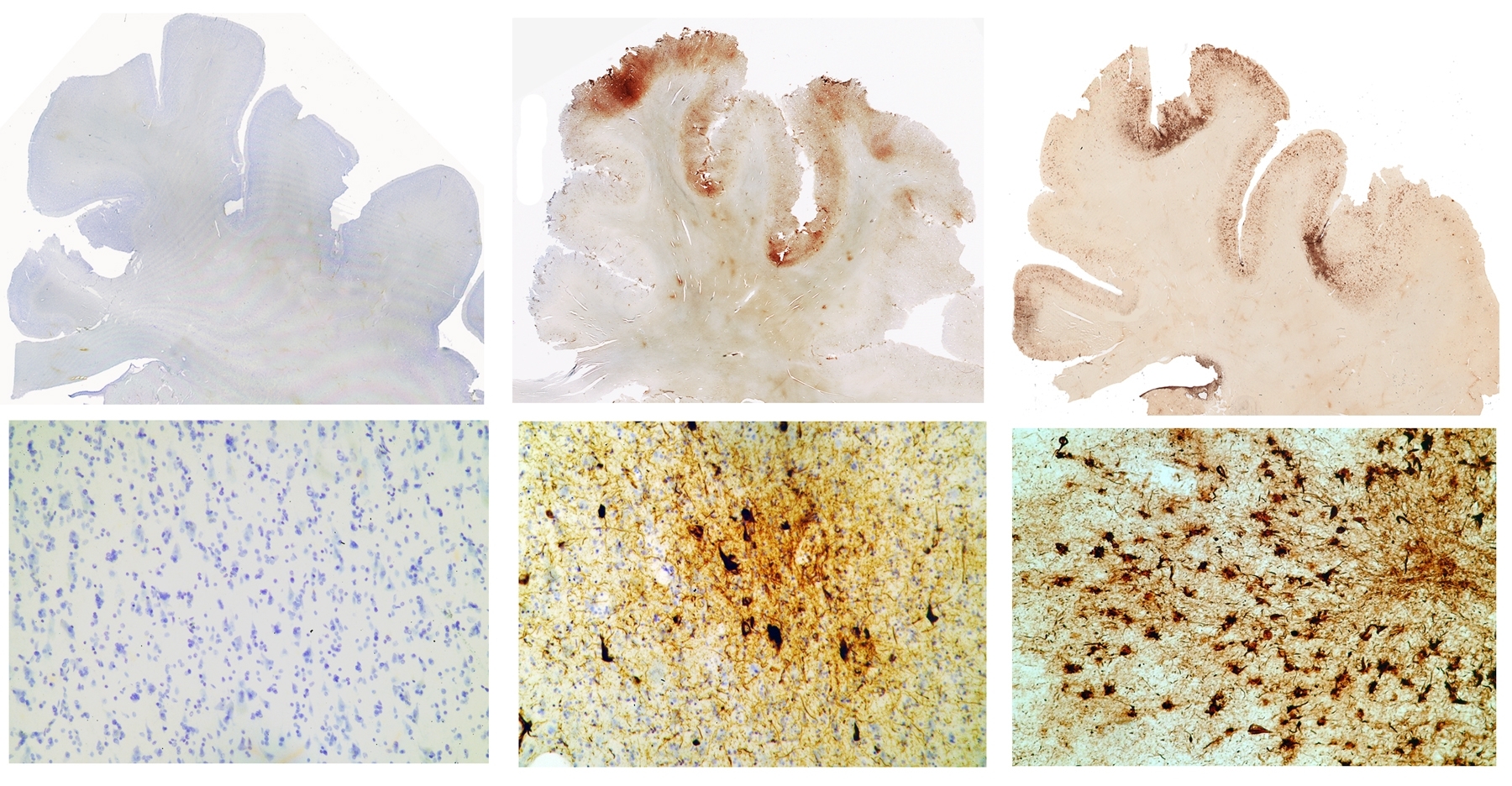

The clinical features of CTE typically manifest years or decades after the initial repetitive traumatic brain injury (RTBI). CTE is characterized by and unique because of specific ways the Tau proteins build up into pathological structures and processes in the brain, such as neurofibrillary tangles, tau-positive astrocytes, and tau-positive cell processes. Neurofibrillary tangles are formed by the hyperphosphorylation (a chemical process) of this protein called ‘tau.’ In a normally functioning brain, tau binds to microtubules (a structural component of our cells) for their formation. When tau is hyperphosphorylated, it cannot bind to the microtubules, which become unstable and disintegrate. The tau, unable to bind, clumps together and creates the neurofibrillary tangles also called intracellular lesions. These tangles tamper with normal brain function, causing the presentation of clinical symptoms (2).

Tau immunostained sections (whole brain section on top, microscopic section on bottom) of the frontal cortex of a control, a former NFL player, and a former boxer (from left to right). Tau is stained in brown. Photo cortesy of Boston Univeristy School of Medicine.

Some presentations of CTE include motor symptoms -- tremor, affected gait, etc. -- like those seen in Parkinson’s disease. Motor symptoms are far more abundant amongst boxers but scarce amongst football players, hockey players, and professional wrestlers. The cause of this is not totally evident, but a possible explanation is the biomechanics of head injury in different sports. For example, in boxing, a traumatic brain injury (TBI) caused by a hook or jab to the jaw causes “angular acceleration and torsional injury involving the brainstem and cerebellum,” while in football, hits more typically involve “transverse and linear acceleration.” It has been noted that many of the motor signs involved in boxing-related CTE are similar to those experienced by individuals with Parkinson’s disease, which impacts coordination and motor functioning as a result of degeneration of the brainstem. Football players with CTE may ultimately experience degeneration of the brainstem and cerebellum, though this would likely occur later in the disease’s progression, and the widespread degeneration they experience elsewhere in their brains could mask motor issues. (1).

CTE is somewhat similar to other tauopathies (diseases with a build-up of tau protein) like Alzheimer’s disease, and they are not always easily distinguishable. However, different behavioral problems seem to be unique to the different diseases. For example, Frontotemporal Dementia usually includes disinhibited or inappropriate behavior and speech, which is much less common in CTE. Diagnoses can be mixed up, and especially because CTE cannot be diagnosed in vivo, a misdiagnosis of Alzheimer’s may be given when CTE is the true cause of symptoms and degeneration.

Note that CTE can lead to dementia but that doesn’t mean that CTE leads to Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s is one disease within a category of disorders called dementias. Dementia refers to a group of memory and cognitive symptoms that can be clinical presentations of a neurodegenerative disease. Click here to learn more about Alzheimer’s and dementia.

It is also important to note that there is significant crossover between the symptoms of post-concussion syndrome (PCS) and CTE. PCS consists of long-term symptoms for more than one month following a concussion or a series of concussions. PCS by definition is temporary though it can be long-lasting, and symptoms should improve over time. On the other hand, CTE is a degenerative disease, so although patients with PCS and CTE may present with similar symptoms, the trajectory for an individual with CTE will be downward and symptoms will not improve. Moreover, PCS directly follows a concussion, while in most cases, the onset of CTE symptoms typically occurs years or decades after exposure to head impacts. Even if one has had a concussion with symptoms that persist for years, they likely suffer from post-concussion syndrome.

1) Stern, R. A., Daneshvar, D. H., Baugh, C. M., Seichepine, D. R., Montenigro, P. H., Riley, D. O., Fritts, N. G., Stamm, J. M., Robbins, C. A., McHale, L., Simkin, I., Stein, T. D., Alvarez, V. E., Goldstein, L. E., Budson, A. E., Kowall, N. W., Nowinski, C. J., Cantu, R. C., Ann C. McKee, A. C. (2013). Clinical presentation of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Neurology. 81 (13) 1122-1129; DOI:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a55f7f

2) Stein, T. D., Montenigro, P. H., Alvarez, V. E., Xia, W., Crary, J. F., Tripodis, Y., Daneshvar, D.H., Mez, J., Solomon, T., Meng, G., Kubilus, C. A., Cormier, K. A., Meng, S., Babcock, K., Kiernan, P., Murphy, L., Nowinski, C. J., Brett, M., Dixon, D., Stern, R. A., Cantu, R. C., Kowall, N. W., McKee, A. C. (2015). Beta-amyloid deposition in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol., 130(1), 21-34. doi:10.1007/s00401-015-1435-y

Executive dysfunctioning: trouble with planning, sequencing, organization, and emotional contro.

Visuospatial: visual/spatial awarenes

Tauopathies: diseases with a build-up of tau protein

In vivo: in a living person